Dr. Amit Anand demonstrates the TMS device on Patty Harshaw, his department's TMS coordinator. / Doug McSchooler / For the Star

The depressed part of Ruth Schwer's brain told her that nothing would help, nothing would break through the stifling malaise. She had tried medications. Each worked for six months to a year, but then, the effect would wear off, and she would plummet back into darkness.

Still, the thinking side of her brain told Schwer, 43, to keep looking for a treatment.

"I felt more and more desperate," she said. "But the rational part says that you've experienced this before, you know it will change."

Then, she found a therapy unlike any other she had tried -- transcranial magnetic stimulation, known as TMS.

The treatment delivers magnetic pulses that produce electricity in her brain. While no one knows for sure how it works, the pulses appear to correct a deficit in the brain's chemical makeup, which over time results in a lifting of the depression.

Approved for use by the Food and Drug Administration four years ago, TMS gives psychiatrists their first-ever tool for patients for whom medications don't work or produce too many side effects. It is not as drastic as electro-convulsive therapy, which can interfere with a person's memory and is usually reserved for people with the most severe forms of depression.

For patients like Schwer, who lives on the Northwestside, TMS can be life-changing.

Schwer has a master's degree and a full-time job. But since puberty, she has grappled with periods of depression that leave her bedridden and isolated.

In the summer of 2010, she decided to try the treatment, which consists of half-hour or so sessions every day for four to six weeks.

Patients settle into a spa chair, and the doctor positions the magnet, a C-shaped device a little larger than the span of your hand, over the left side of the skull, next to the part of the brain that governs mood.

The NeuroStar TMS machine then administers treatment for four seconds, rests for 26 seconds and fires again. The pulses are thought to stimulate the neurons in the area, which prods them to release neurotransmitters, which over time will improve mood in many patients.

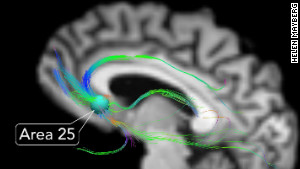

Depression doesn't stem from a lack of one chemical in the brain but from the workings of the brain's circuit as a whole, doctors think.

"It's the same as how electricity is produced through turbines. . . . The brain is also a conducting organ," said Dr. Amit Anand, director of the TMS and mood disorders programs at Indiana University Health. "It is a different way of thinking about depression. . . . We can straight away treat the organ, the brain, which is involved in depression, rather than the whole body."

The treatment sensation is not pleasant, say some who have gone through it. It's like "noogies," said Dr. Christopher Bojrab, a psychiatrist in private practice in Indianapolis, who has tried it.

As compared with other therapies, including medications, side effects other than the discomfort are minimal, experts say. A very small number of cases have resulted in seizures.

Schwer recalled it feeling more like a woodpecker sitting inside her temple.

"The odd thing is that the pressure was coming from the inside of your head, not the outside," she said.

Over time, however, she got used to the sensation, and it did not bother her.

Then about the third week of treatment, she woke up one day and realized she was smiling.

"I realized I had the freedom to direct my attention to where I wanted it to go," she said. "Having the option to experience happiness and joy, I felt like something had definitely changed for me."

Schwer remains on medication, but at a lower dose. And most exciting, her prescription has not changed for more than a year. She said it's easier to interact with strangers or try new things, like signing up for an African drumming class.

In the past year, she was also able to undergo surgery to correct her congenitally malformed hips.

"I felt like there was a point to getting better," she said. "In my previous mental state, I would have said, 'Yes, I'm in pain, but what does it matter? It's not going to get better, you just have to live with it.' "

TMS may not be for everybody. Treatments aren't cheap, and many insurers don't cover it. Patients can expect to pay upwards of $6,000.

Nor does it help everybody. To qualify, one must have tried and failed to address the depression with medication.

About a third of those people who try TMS will see their symptoms completely disappear, said Dr. Mark George, a spokesman for the American Psychiatric Association, who has studied TMS since 1993.

Once people have undergone treatment, they may need a follow-up session or two, but some people enjoy results for years. And, if they return five or six years later, undergoing therapy again often helps, said George, a research psychiatrist at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Bojrab, who has been offering the therapy for about two years, said that none of the 20 patients he's treated has returned. Out of those 20, three showed no response, half had a good response, and seven enjoyed complete remission; some even stopping their medications.

Before she underwent the treatment at IU Health, Jan Tobias, 56, had hoped she would fall in the latter camp. More than halfway through, it became clear that would not be the case.

Nor did she experience what she would define as a complete turn-around. Still, partway through, the Nappanee grandmother, who has battled depression most of her life with little relief from pharmaceuticals, saw a change.

"I had days of a difference where it was night and day. It was like opening my eyes for the first time," she said. "Everything was brighter, everything was new. I was thinking, 'Is this how it's really supposed to be?' Then the next day or two days, I would fall back."

But her husband said he had noticed a difference. And now, after going through the treatments last summer, Tobias can function once more.

"It's a new world for me . . . The main thing is, all you want to do is gain hope, and the rest can come later," she said. "That was my main goal, to gain hope in life."

http://www.indystar.com/article/20120429/LIVING01/204290304/When-meds-fail-magnetic-therapy-shows-promise-treating-depression

Still, the thinking side of her brain told Schwer, 43, to keep looking for a treatment.

"I felt more and more desperate," she said. "But the rational part says that you've experienced this before, you know it will change."

Then, she found a therapy unlike any other she had tried -- transcranial magnetic stimulation, known as TMS.

The treatment delivers magnetic pulses that produce electricity in her brain. While no one knows for sure how it works, the pulses appear to correct a deficit in the brain's chemical makeup, which over time results in a lifting of the depression.

Approved for use by the Food and Drug Administration four years ago, TMS gives psychiatrists their first-ever tool for patients for whom medications don't work or produce too many side effects. It is not as drastic as electro-convulsive therapy, which can interfere with a person's memory and is usually reserved for people with the most severe forms of depression.

For patients like Schwer, who lives on the Northwestside, TMS can be life-changing.

Schwer has a master's degree and a full-time job. But since puberty, she has grappled with periods of depression that leave her bedridden and isolated.

In the summer of 2010, she decided to try the treatment, which consists of half-hour or so sessions every day for four to six weeks.

Patients settle into a spa chair, and the doctor positions the magnet, a C-shaped device a little larger than the span of your hand, over the left side of the skull, next to the part of the brain that governs mood.

The NeuroStar TMS machine then administers treatment for four seconds, rests for 26 seconds and fires again. The pulses are thought to stimulate the neurons in the area, which prods them to release neurotransmitters, which over time will improve mood in many patients.

Depression doesn't stem from a lack of one chemical in the brain but from the workings of the brain's circuit as a whole, doctors think.

"It's the same as how electricity is produced through turbines. . . . The brain is also a conducting organ," said Dr. Amit Anand, director of the TMS and mood disorders programs at Indiana University Health. "It is a different way of thinking about depression. . . . We can straight away treat the organ, the brain, which is involved in depression, rather than the whole body."

The treatment sensation is not pleasant, say some who have gone through it. It's like "noogies," said Dr. Christopher Bojrab, a psychiatrist in private practice in Indianapolis, who has tried it.

As compared with other therapies, including medications, side effects other than the discomfort are minimal, experts say. A very small number of cases have resulted in seizures.

Schwer recalled it feeling more like a woodpecker sitting inside her temple.

"The odd thing is that the pressure was coming from the inside of your head, not the outside," she said.

Over time, however, she got used to the sensation, and it did not bother her.

Then about the third week of treatment, she woke up one day and realized she was smiling.

"I realized I had the freedom to direct my attention to where I wanted it to go," she said. "Having the option to experience happiness and joy, I felt like something had definitely changed for me."

Schwer remains on medication, but at a lower dose. And most exciting, her prescription has not changed for more than a year. She said it's easier to interact with strangers or try new things, like signing up for an African drumming class.

In the past year, she was also able to undergo surgery to correct her congenitally malformed hips.

"I felt like there was a point to getting better," she said. "In my previous mental state, I would have said, 'Yes, I'm in pain, but what does it matter? It's not going to get better, you just have to live with it.' "

TMS may not be for everybody. Treatments aren't cheap, and many insurers don't cover it. Patients can expect to pay upwards of $6,000.

Nor does it help everybody. To qualify, one must have tried and failed to address the depression with medication.

About a third of those people who try TMS will see their symptoms completely disappear, said Dr. Mark George, a spokesman for the American Psychiatric Association, who has studied TMS since 1993.

Once people have undergone treatment, they may need a follow-up session or two, but some people enjoy results for years. And, if they return five or six years later, undergoing therapy again often helps, said George, a research psychiatrist at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Bojrab, who has been offering the therapy for about two years, said that none of the 20 patients he's treated has returned. Out of those 20, three showed no response, half had a good response, and seven enjoyed complete remission; some even stopping their medications.

Before she underwent the treatment at IU Health, Jan Tobias, 56, had hoped she would fall in the latter camp. More than halfway through, it became clear that would not be the case.

Nor did she experience what she would define as a complete turn-around. Still, partway through, the Nappanee grandmother, who has battled depression most of her life with little relief from pharmaceuticals, saw a change.

"I had days of a difference where it was night and day. It was like opening my eyes for the first time," she said. "Everything was brighter, everything was new. I was thinking, 'Is this how it's really supposed to be?' Then the next day or two days, I would fall back."

But her husband said he had noticed a difference. And now, after going through the treatments last summer, Tobias can function once more.

"It's a new world for me . . . The main thing is, all you want to do is gain hope, and the rest can come later," she said. "That was my main goal, to gain hope in life."

http://www.indystar.com/article/20120429/LIVING01/204290304/When-meds-fail-magnetic-therapy-shows-promise-treating-depression